In 2019, drug pricing was expected to be a top drug industry issue heading into the New Year. Things changed in 2020. The pharma industry (and the whole world) was…well…slightly distracted.

In 2019, drug pricing was expected to be a top drug industry issue heading into the New Year. Things changed in 2020. The pharma industry (and the whole world) was…well…slightly distracted.

Drug pricing, however, didn’t just simply disappear as an issue. In the U.S., skyrocketing drug prices are as much a hot-button issue as ever, with the nation spending more than $500 billion a year on prescription medicines.

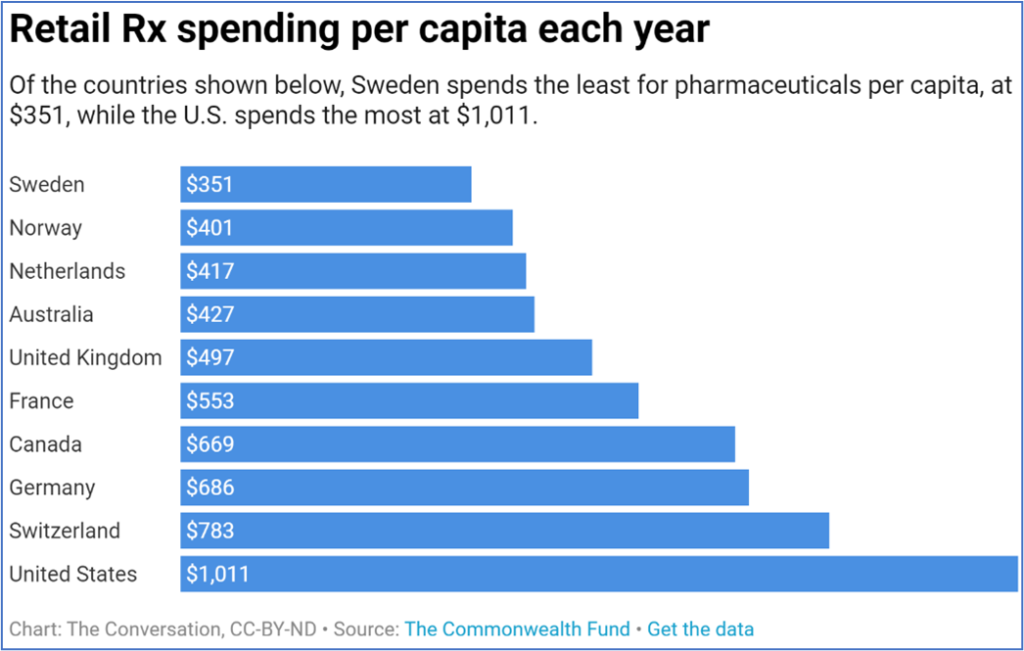

U.S. spending on drugs may be high, but U.S. use of prescription drugs is not. From a 2019 article at The Conversation:

“[I]t is not like Americans are overly reliant on prescriptions drugs as compared to their European counterparts. Americans use fewer prescription drugs, and when they use them, they are more likely to use cheaper generic versions. Instead the discrepancy can be traced back to the issue plaguing the entirety of the U.S. health care system: prices.”

Policies and proposals to solve abnormally high prices abound. President Trump’s Most Favored Nation model, which would have slashed “drug pricing through a nationwide ‘demonstration program’ based on the lowest price in 22 countries of 50 widely used drugs in Medicare” was recently blocked from implementation. President Biden had previously endorsed different legislation which would “cap drug prices based on an index of six countries, and empower the Secretary of HHS to negotiate for further discounts.”

Is Drug Pricing Regulation Beneficial?

Is Drug Pricing Regulation Beneficial?

In the cases of the proposals supported by both U.S. Presidents, there is much apprehension over who will end up paying the difference when it comes to regulated pricing. Concerns that doctors will switch patients to cheaper – and perhaps less effective – drugs swirl around worries that less commonly prescribed drugs may see prices rise to offset the decreases.

Price regulation, however, isn’t all bad. In fact, it can be quite important. One example would be the price of hepatitis C vaccines in the U.S.

A 12-week course of antiviral treatment for hepatitis C – which can eliminate the virus from the body – can cost as much as $84,000. A single Sovaldi pill (one of the hepatitis C antivirals) is reported to cost as much as $1,000. While the introduction of generics or other competing products generally helps drive prices lower, there are still limits on when – and even if – a U.S. health insurer will cover treatment. It has been noted that where drug purchasing power is low, regulation could be helpful – such as in the case of hep C vaccines in the U.S.

There is certainly another side to this model. Where health insurance coverage is in place for a majority of people, increased regulation can be less helpful…and may, in fact, become intrusive or harmful. Over-regulation can stifle industry innovation, and restrain the investment needed to fund drug discovery, development, clinical trials and commercialization.

The U.S. healthcare system has a reputation as a hands-off, high-cost-driven, free enterprise system. But it also illustrates how legislation and regulation can play an important role in furthering drug availability and affordability. There have been numerous programs such as the Orphan Drug Act (itself responsible for bringing hundreds of medicines to the market which otherwise would never have been developed), the Hatch/Waxman Act (which paved the way for much broader availability of generics), and many other initiatives.

The smaller the GDP, the bigger an issue drug pricing is.

Drug pricing is an issue that is magnified in smaller countries. Some nations, and especially those in the third world, struggle with higher prices. One study by the Center for Global Development found that some poor countries pay 20-30X more for basic medicines than others. This included the generic heartburn medicine omeprazole, and the pain reliever acetaminophen (paracetamol). One reason this occurs is safety:

“In many developing countries more expensive brand-name generics are widely used, because people are concerned about unsafe or counterfeit drugs. In the poorest countries, unbranded generics are only 5 percent of the pharmaceutical market by volume—in comparison to the US where unbranded quality-assured generics are 85 percent of the market by volume.”

“A robust market for generic drugs is a core part of an affordable health system. But in way too many countries, generic drug markets are broken and patients are paying the price,” said Kalipso Chalkidou, the director of global health policy at the Center for Global Development and an author of the study. “You need enough competition to keep prices low and quality assurance that consumers trust, or essential medicines are going to be much more expensive than they should be.”

From: New Study Finds Some Poor Countries Paying 20 to 30 Times More for Basic Medicines Than Others

This is the case in India, where branded generics – as opposed to unbranded generics – are widely used. What is the difference between a branded and unbranded generic? According to an article at Pharmacy Times (Branded Generics: Misunderstood, but Lucrative):

“Branded generics are prescription products and are not authorized generics, which are drugs made by or under license from the innovator company and sold without a brand name… IMS Health, which began tracking and reporting on branded generics in 2002, defines the category as including prescription ‘products that are either novel dosage forms of off-patent products produced by a manufacturer that is not the originator of the molecule, or a molecule copy of an off-patent product with a trade name.’ This definition is used by both the FDA and the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS).”

The Challenges and Complexities of Regulating Drug Prices

The Challenges and Complexities of Regulating Drug Prices

A 2019 article by Stan Fleming at Forbes discussed the challenges of regulating drug prices:

“As difficult as compromise will be for an industry that is falling short of sustainable growth, it will also be a challenge for pricing boards. If affordability is the mandate, regardless of how low commissions set prices, they will face pressure to go farther still. Markets steer capital to where the need, and hence the value, is highest. Controls would do the opposite. The higher the medical need and the more patients treated, the greater will be the pressure to reduce prices.”

The bottom line is that drug pricing isn’t a binary issue in which you either support unfettered free market solutions or inflexible, obstructive regulation. There needs to be a middle ground. It’s a complex issue. As Fleming indicates, “Price controls would improve access to existing drugs through lower costs but reduce productive capacity.”

A balance will need to be found that allows for more realistic pricing – especially in those smaller countries which suffer from exponentially more expensive drugs, and in larger nations where certain drugs without competition are priced out of reach. The challenge, as it always is, will be to craft legislation which helps patients while averting negative impacts on the pharma industry…impacts which ultimately trickle down to the very patients such legislation is intended to help. One way to achieve this would entail some degree of regulation of essential lifesaving drugs in developing countries, while de-regulating other drugs generally.